Is there a place for aesthetics in contemporary art? Aesthetics – conceived not simply as investigations into what we find beautiful or sublime, but as the study of sensory experience in all its wealth – is a rich field that will never turn obsolete. As long as art is concerned with its appearance, its sensory effect on the viewer, it is concerned with aesthetics. Whether it is impressionism with its studies of ambient light, the gestures of action painting, the arid compositions of hard edge painting, the specific objects of minimalism, or the shallow and stylised forms of pop art, there is a concern with visual form. Immaterial works of conceptual art do not have any determinate visual presence, although some poetic textual descriptions (think of Yoko Ono's Fluxus text pieces, for instance) contradicts the assumed disregard for aesthetic effect. However, in much contemporary art, the aesthetic component becomes subsidiary to the topic under investigation.

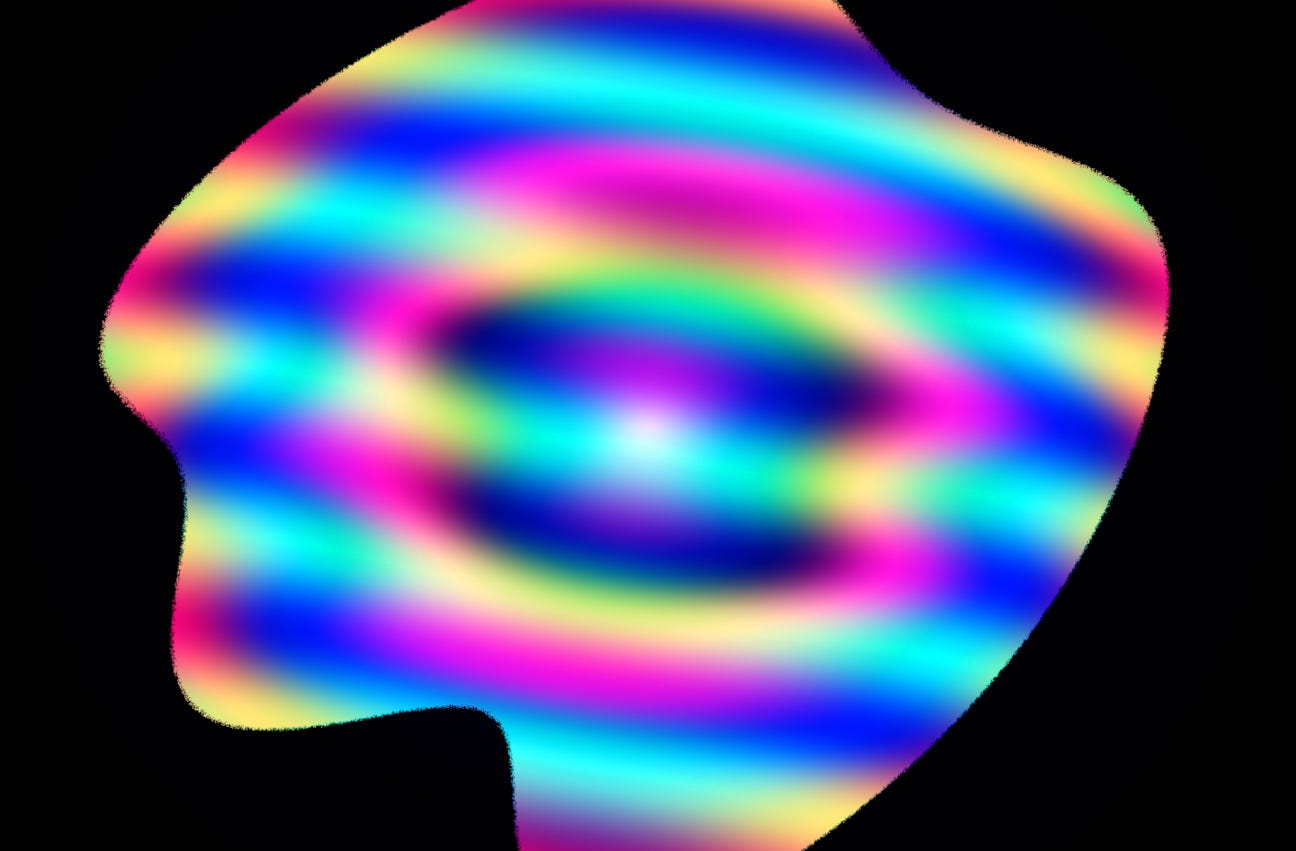

Colour Revolution #4 (2022), video still.

It is possible to criticise art for having abandoned aesthetics and sensual appeal, and having become emptied of emotions. But there is a potential paradox in such a criticism, as art critic and philosopher Laurent Buffet has pointed out in a recent book (which I haven't as much as held in my hands, I'm taking this from a review by Christian Ruby). These critics deplore the disappearance of that which qualifies as art according to their definition; while they regret that contemporary art doesn't cultivate the beautiful, they denounce the aestheticisation of society.

Mais Buffet pointe à ce sujet un paradoxe : d'un côté, ces auteurs déplorent la disparition de l'art — du point de vue de leur propre définition —, mais de l'autre, ils déplorent que la société toute entière soit désormais soumise au régime esthétique de l’art. Dans la même veine, ils regrettent que l'art contemporain ne cultive plus le beau, mais fustigent l'esthétisation de la société.

However, the aestheticisation of the world isn't the consequence of (or a compensation for) art's abandonment of aesthetics, according to Buffet; on the contrary, art has relinquished aesthetics as a reaction against a colonisation of society by a uniform aesthetics governed by marketing. Contemporary art thus finds its critical power by escaping the logic of having to satisfy aesthetic needs.

The opposition against aesthetics runs in parallel with a differentiation against commercial contemporary art, the kind of works that may find an owner almost regardless of what it looks like as long as it can be hung over a sofa. There is an understandable scepticism against this auction house art, which for a while was perhaps the public face of contemporary art, despite the fact that it isn't representative of its core forms such as performances, installations, participatory projects, and video art, all of which lend themselves poorly to commerce.

An artist whose project deals with aesthetics in the sense I'll discuss here is James Turrell. In one of Turrell's installations, Ganzfeld, one enters a blue, empty, seemingly endless space. There is a cavity, a smoothly but steeply sloping pit in the floor, impossible to say how deep. There must be a wall on the other side of the pit, but again, impossible to say how far away. Entering this installation, one becomes aware of one's sense of sight, or rather its insufficiency for grasping the environment with its contradictory cues. Vision is not enough; one has to take a step forward but not too far, then a step back again, and all it results in is dizziness. It works like an instant practical demonstration of phenomenology, in which you are forced to bracket out what you know about the world and only take heed of immediate sensory impressions – or maybe it works even more like a practical joke, since you don't really know for sure what the proportions of this space are, and neither vision alone nor vision amended with moving reveals more with any certainty.

Gernot Böhme (1937–2022) is one of the few who have made substantial and original contributions to aesthetics in recent times. His writing is remarkably lucid for a philosopher, without overly simplifying or introducing complications where none are needed. Perhaps it is because of the many concrete examples he always keeps close at hand that his writing is so accessible. Maybe it has something to do with the fact that in addition to philosophy, Böhme also studied physics and mathematics, disciplines that impose a certain intellectual rigour and clarity; yet it is precisely an alternative to such forms of knowledge he tries to develop.

Aesthetics as a discipline has neglected its very basis, the study of sensory perception, Böhme argues. From the beginning, aesthetics was proposed as a complementary path of knowledge besides logic. As the founder of aesthetics, Baumgarten, wrote:

Wenn man bei den Alten von der Verbesserung des Verstandes redete, so schlug man die Logik als das allgemeine Hilfsmittel vor, das den ganzen Verstand verbessern sollte. Wir wissen jetzt, daß die sinnliche Erkenntnis der Grund der deutlichen ist; soll also der ganze Verstand gebessert werden, so muß die Ästhetik der Logik zur Hilfe kommen. (Quoted in Böhme, 2000, p. 13)

Very roughly: To improve reason (or the intellect) in its totality, logic used to be proposed as the tool. We now know that sensory knowledge is the basis of clarity; to improve the full intellect, aesthetics must come to the aid of logic.

It is this little pursued path of aesthetics that Böhme continues on. He distinguishes between Ästhetik as the sub-discipline of philosophy devoted to art, beauty, and taste, and Aisthetik as a theory of sensory perception. The cultivation of sensory perception as a means of knowing stands as an alternative to the intellectual and scientific approach of measuring and calculating or reasoning without directly engaging the senses. According to Böhme, traditional aesthetics is insufficient as aisthetics, because it downplays the role of the senses in its emphasis on intellectual judgement.

Böhme's most famous concept is the atmosphere, an enveloping, multi-modal, synaesthetic first impression of an environment or a situation. The atmosphere as such is perceived first, and globally, before we disentangle its constituent elements into separate objects and into perceptions that belong to specific sensory modalities.

Presumably, atmospheres should be subjectively experienced, but there are times, Böhme points out, when we experience a discrepancy between our own mood and the atmosphere. Feeling gloomy on a beautiful sunny spring day is one such example. Therefore, Böhme argues, atmospheres are not entirely subjective but also have an objective component.

Likewise, objects have a subjective and an objective pole. Objects have properties (Eigenschaften) which remain constant and belong to them. This is different from what we perceive of an object in any given moment, that which Böhme calls Ekstasen, or literally the coming-out-of a thing, which is the way its presence becomes perceptible.

Böhme also resuscitates the old notion of physiognomy, which has a troublesome past connection to phrenology, originally a theory that tried to find character traits in physical attributes. Again, there is a discrepancy between outwards characteristics and personality, although we rapidly pass judgements on individuals based on their look. Unfortunately, a first impression tends to stick, even as we gradually get to know other sides of the person. This process is well known in psychology, as discussed in Kahneman's Thinking, Fast and Slow. In one study, faces were shown in brief glimpses and the participants were able to assess how likable or trustworthy the person was. As it turns out, facial traits indicating competence is a good predictor of success in elections. ”The faces that exude competence combine a strong chin with a slight confident-appearing smile. There is no evidence that these facial features actually predict how well politicians will perform in office,” Kahneman notes (p. 91).

Böhme uses two words which both translate as reality, but reflecting the difference between objective and subjective: Realität vs. Wirklichkeit, which he relates to Joseph Albers' concepts of factual fact and actual fact. In Albers' colour theory, the physical pigment on canvas and the measured wavelengths of colours are factual facts, or Realität, whereas the perceived colour, which depends on many factors including surrounding colour fields, reflecting properties, and ambient light, is an actual fact. Maybe ”acting fact” would be closer to the meaning of the word Wirklichkeit, with its connotations of working or functioning, being active, as in the related verb form wirken. It should not be confused with appearance, for which there is the word Erscheinung. Turrell's light installations really make a point of the difference between actual fact and factual fact, through dematerialised pictures made of light and floating in space as if seen through a window, or, as Böhme writes:

Auf andere Weise hat der Künstler James Turrell die Differenz von actual fact und factual fact auf die Spitze getrieben, indem er Bilder produzierte, die keinen Bildgegenstand mehr haben. Es handelt sich um im Raum schwebende Lichtgebilde bzw. eine farbige Tönung eines ganzen Raumes, in den man wie durch ein Fenster hineinblickt. (pp. 57–8)

Wirklichkeit also corresponds to our socially constructed reality, which is no less real or consequential for that reason. A symbol, Böhme explains, is a sign which is what it signifies. Insignia of royalties and money are two examples. Money, as in bank notes, signifies economical value but it also has the same value. Since the abolishment of the gold standard, the value of money is made up entirely of everyone's belief in it. Even gold seems to possess a value mostly determined by social agreement, although it also has real use value. Apart from use value and exchange value, there is a third form of value, related to the image or associations of commercial products, it is what Böhme calls Inszenierungswert, which might be called an aesthetic value.

Whereas the renewed aesthetics of Böhme finds obvious applications to the aesthetics of nature and design, as well as the aestheticisation of politics and the commercial sphere, Böhme has relatively little to say about art; besides the passage on Turrell there is a brief analysis of a Caspar David Friedrich painting and a mention of Duchamp. The reason is that art usually requires interpretation, it engages hermeneutics and semiology in the viewer's process of making sense of signs and symbols, and thinking about the author's intention, which are not fundamentally aesthetic activities in the meaning of activating the senses. But, as the example of James Turrell's installation shows, there are current art projects that have everything to do with aesthetics.

References

Gernot Böhme: Aisthetik. Vorlesungen über Ästhetik als allgemeine Wahrnehmungslehre. Fink, München 2001.

Daniel Kahneman: Thinking, Fast and Slow. Penguin, 2011.

https://ekebergparken.com/en/skyspace-ganzfeld-james-turrell