Julian Assange is finally free. Journalism is not a crime, nor is engaged political art illegal yet. But how efficient is it?

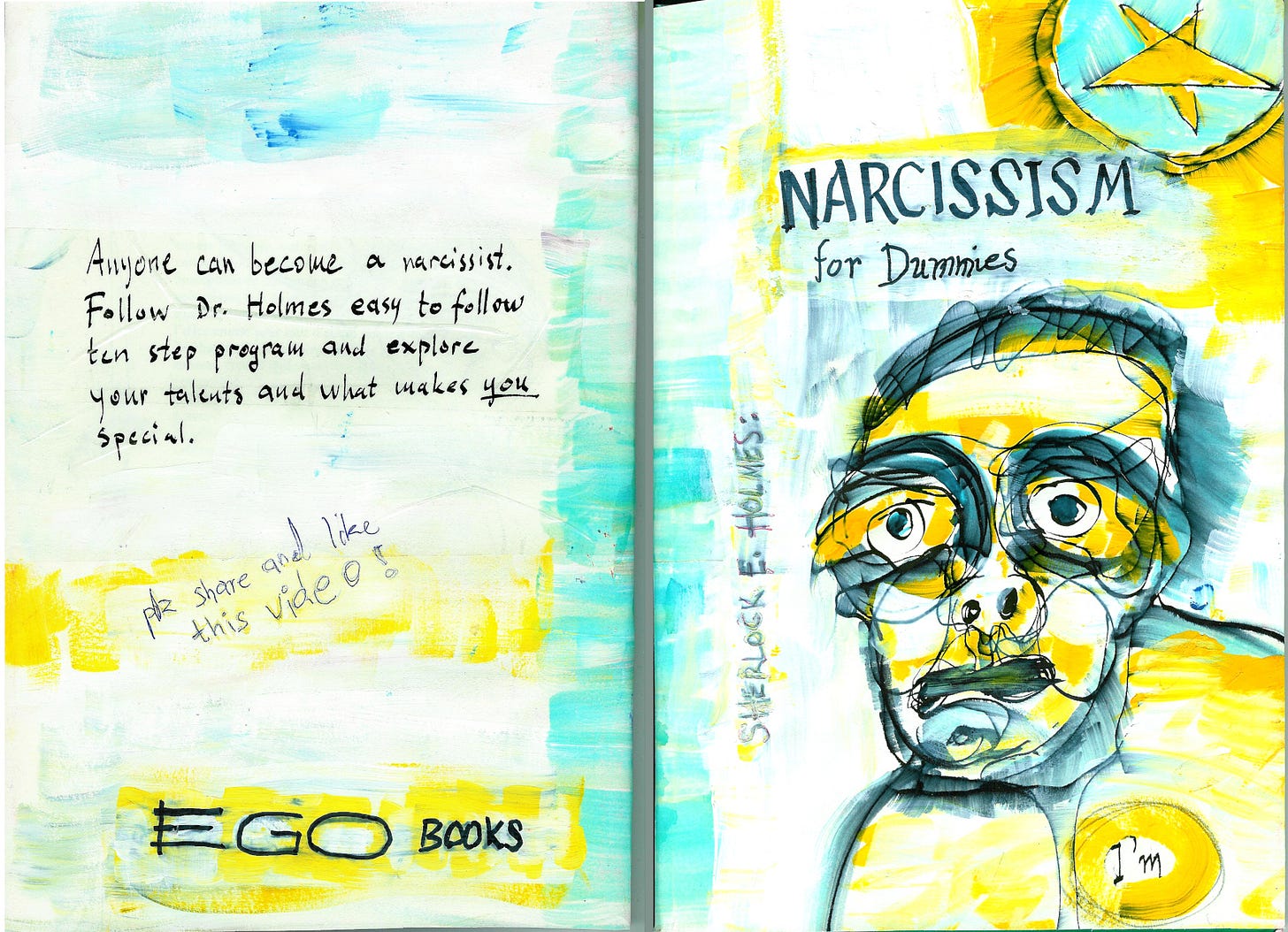

One of the fictional book covers on display in the Safe-space for Narcissist installation, 2019.

Does art ever have a transformative power? Can the exposure to works of art really change the viewer in some fundamental respect? Most artists working with political or engaged art probably think that is true, and more or less consciously work in the hope that what they do will have some sort of positive effect. Otherwise their purpose would be mere virtue signalling. But if their main audience already largely share their world view, which is not an unreasonable assumption, then the artist is only preaching to the choir. The viewer's opinions may be reinforced rather than challenged, whereas those who strongly disagree with the agenda will absolutely not be swayed in their beliefs by a work of art. They will rather oppose it and might even call for the artist to be cancelled or demand the de-funding of the institution that exhibits the art.

That is not to say that political art is futile. It's just that its effect as soft power competes with so many other, and so much louder voices, such as the spin campaigns of corporations, think tanks, and governments. On the other hand, it may join forces with grass-roots activism and street protests which are visible in a way that becomes hard to ignore, although mainstream media may do their best to neglect huge demonstrations.

Then there is the debate, or the ambivalence, about the efficacy of art as political force on one hand, and the potential pitfall of art being debased into one-dimensional propaganda messaging on the other hand, which is always a risk when ambiguity and complexity are abandoned in favour of loud and clear messages. My impression of activist artists is that the concern for "quality" of art as gauged in strictly aesthetic terms or by any intra-artistic criteria is not something they worry a great deal about when there is an important struggle to engage in. Artists simply use art as their tool in campaigns because it happens to be their field of competence, and the quality of the art doesn't necessarily suffer for taking on some important cause. Conversely, some believe that art becomes more valuable by demonstrating an engagement in the right kind of issues.

I will discuss a few examples of political/activist art related to Assange and Wikileaks, some of which I discovered while working on my book (forthcoming, I'd like to say – still looking for a publisher), but first I would like to recall some facts related to the case.

How Julian Assange escaped extradition

The prosecution of Julian Assange has finally ended, quite abruptly and in a way few could have imagined. Of the 17 charges of violation of the Espionage Act all but one were dropped in a plea deal in which Assange pleaded guilty to the charge of conspiracy to obtain defence information. Over the fourteen years during which Assange was stuck, first, in the Ecuadorian Embassy in London, and then held at the Belmarsh maximum security prison, the long list of ill-treatment, public smears, malpractice of justice, surveillance, and even plots to kidnap or assassinate Assange is more typical of an authoritarian state than the so-called "democracies" where this played out. For those who are not already familiar with all the details, the whole story is well worth an in-depth study. Lissa Johson's five part series from 2019 provides many interesting insights. It will educate you about the principle of might-makes-right, or "the rules based order" as it is also known, and how any resemblance of due process may be turned into a legal farce of revenge, carried out by the same powers whose war crimes Assange helped uncover. And not least, it is instructive to see how such a diligently carried out character assassination can be so effective.

Negotiations between representatives of the Australian government and the White House had been going on behind the scenes for some time, with the Australian government being pushed by a growing popular opinion in favour of Assange's return home to Australia. The result is far better than most would have dared to hope. There is no gag order or restriction on movement, no more sentence to be served, a guarantee of no more charges related to any of his previous publications up to the moment of the plea deal; however, Assange was ordered to destroy any unpublished material with information related to the US that may still be in Wikileaks' possession.

A court hearing in London was scheduled for early July, in which Assange would have appealed his extradition to the United States on two grounds, as Joe Lauria explains:

1). his extradition was incompatible with his free speech rights enshrined in the European Convention on Human Rights; and 2.) that he might be prejudiced because of his nationality (not being given 1st Amendment protection as a non-American).

No-one expected that Assange would be granted free speech rights in a US court, in other words, the right to explain why he did what he did. Apparently it was the British High Court's decision in May to grant an appeal hearing on that question that sped up the intense negotiations behind the scenes. Allowing Assange to recount in an American court room CIA's surveillance of the Ecuadorian embassy and plots to kill or kidnap him in the middle of London simply would not be a palatable prospect. Had Assange been extradited, he would have been sent to the court in Eastern district of Virginia, notorious for its high conviction rate in national security cases, explained by the concentration in this court district of private security contractors, military industry complex, and three letter agency employees. In other words, the plea deal happened because of the embarrassment a court case in the US would cause the government.

Besides, as Biden is seen fumbling and gaffing and, worse, being complicit in war crimes by helping Israel destroy what little there remains of Gaza, he could use a PR stunt to paint him in a more humane light, which the release of Assange perhaps contributes to. At the same time the plea deal means that the US government can save face. Or, more accurately: their humiliation is not as complete as if all charges were dropped and Julian Assange pardoned, a goal which might be pursued later.

Crucially, a plea deal does not create juridical precedence. This is significant for the chilling effects on national security journalism, which has been at stake all the time in this case. WikiLeaks publishes documents of public interest sent to them, in that respect they are no different than other journalists. Hence, prosecuting WikiLeaks for receiving and publishing secret documents would imply that any journalist could be found guilty of espionage for receiving the wrong kind of information from their sources. But the damage is probably already done; only the most daring journalists will touch national security matters knowing what law-fare processes might be directed at them.

At their best, mainstream media have provided a half-hearted and intermittent support for Assange and Wikileaks. The Guardian, once a respectable publication, first collaborated with Wikileaks in publishing some documents, but then contributed to the character assassination or at least grave misrepresentation of Assange. This appears illogical given the dire consequences for free journalism if the case had resulted in a full conviction, unless one considers the mainstream journalists by the epithet often used by their independent colleagues – as stenographers of power. The smear campaigns against Assange were largely successful in dampening the enthusiasm among some activists on the left. Nevertheless, WikiLeaks and Assange have gained many supporters, not least among independent journalists and activists who have followed the case closely. Without the supporters and their relentless organising over many years, Assange would not be free. Sometimes protest actions have an effect, but not always. It was not of benevolence that the US dropped most of the charges, it was because of the public pressure that shamed them into doing so.

Art projects for Assange

Among all the actors involved in support for Assange, the role of artists should not be forgotten. Clearly the celebrity status of a musician like Roger Waters helps to make his engagement more influential by drawing large crowds, in addition to the fact that he has been exceptionally knowledgeable about the case. Various visual artists have also shown their support for Assange through their projects, some of which have reached a certain notoriety. A partial list can be found at Artists for Assange.

An early, still memorable example is the mail art project Delivery for Mr Assange by !Mediengruppe Bitnik (2013). At the time, Assange was already stuck in the Ecuadorian Embassy. The project documents the delivery of a parcel sent to the Embassy using a camera mounted inside, which automatically took photos every ten seconds. After a lot of suspense (will the parcel reach its destination, will the battery still be charged?), the end is particularly touching. Postal art is contagious.

Cornelia Sollfrank's À la recherche de l'information perdue (2016) is a performance lecture on topics such as information, technology, and feminism, with more or less obvious references to WikiLeaks and Assange.

Ai Weiwei's postcard with the picture of a treadmill which Assange had given him in 2016 is seemingly a more innocuous work. Nevertheless the British arts organisation Firstsite had turned down Weiwei's submission of Treadmill for an exhibition in 2021, coinciding in time with court hearings in Assange's extradition case. The postcard itself is nothing remarkable. If it were not for Ai Weiwei's celebrity and Firstsite's rejection there might not be very much to say about it. The picture on the postcard doesn't tell much of a story on its own, we have to listen to what the artist has to say about it. This is a perfect example of the kind of symbolic work so prevalent in contemporary art, where the work as such really doesn't divulge what it supposedly is about. How could anyone guess that a treadmill somehow is a reference to Assange without having heard the story? In the hands of another artist, the same treadmill might be about body ideals.

A completely different example is Davide Dormino's famous bronze sculpture group Anything to Say? - A Monument to Courage (2015). Edward Snowden, Chelsea Manning, and Julian Assange are portrayed standing on chairs, and then there is a fourth chair, left empty and ready for anyone to step up and raise their voice. The work was first shown in Berlin, and has since toured many European capitals and taken a trip to Australia.

Here the message is much more obvious in the work itself, although the significant function of the fourth chair still needs to be explained. As a monument in public space, it differs from regular monuments not only by depicting whistle blowers and peace activists rather than "war heroes" (sorry for the misnomer), but also by inviting to participation through performance, speech, and mass gatherings. Thus it manages the odd feat of bridging traditional sculpture with relational aesthetics, where the viewer is not a passive spectator but an active participant.

An even more pedagogical project is the installation Belmarsh Live by Manja McCade in collaboration with Tom Aslan. The installation is simply a replica of the prison cell where Assange spent five years, featuring an audio recording from the prison.

The NoisyLeaks! exhibition in Berlin in October 2022 showcased several artists with works more or less directly related to WikiLeaks. And right outside the gallery the Belmarsh Live installation could be visited. As Manja McCabe explains, the original plan was to let visitors stay for 30 minutes locked into the cell, but most could stand it only for four to five minutes.

Andrei Molodkin, known for his works using blood and crude oil for their symbolic significance, took to the drastic strategy of holding an art collection hostage; if Assange would die while in prison the collection would be destroyed by a "kill switch." The valuable collection was said to contain works by Picasso, Rembrandt, and Warhol (though it is unclear which ones), as well as several contemporary artists such as Andres Serrano, Santiago Sierra, and Sarah Lucas. Molodkin, who lives in the small town Cauterets in France, had installed a Swiss bank safe with five locks, and a mechanism used in embassies to automatically destroy sensitive documents consisting of two barrels, one containing acid powder and the other an accelerator which would cause a chemical reaction that would destroy the contents in the safe within hours. The owners of the works in the collection must surely be relieved that Assange is free and alive. As a negotiating strategy, it may appear naïvely optimistic to assume that those who have persecuted a journalist for revealing embarrassing truths about them would care much if a few works of art were destroyed. And had the collection been destroyed, it would have been too easy to put the entire responsibility on Molodkin. Nevertheless, it was one of several means at disposal to build up the pressure to finally release Assange.

A lot of street art also has been dedicated to Assange, some of which has circulated widely on the internet. Unlike so many other political prisoners, he was never completely forgotten. That is why he is now free.

With this rare success story in mind, we can again assess the possibility of art having a real impact. The art projects, even those like Dormino's sculpture group which has toured several cities and has been seen by many, are but a minuscule part of all organising efforts including mass demonstrations and rallies, articles, and videos with panel discussions. But art may reach a different audience who wouldn't go to the demonstrations or watch the videos.

According to the romantic/modernist myth, which I might slightly exaggerate for the sake of argument, the artist is a genius and truth teller, able to see and express things no-one else is able to see. The artist is an exceptional visionary who can transform society through enlightenment. That is not so in today's actionist art, where the artist is but one of a collective who are all aware of the situation and who understand what needs to be done. Artists may have the advantage of knowing how to express these sentiments in a striking form. Furthermore, the naïve expectation of the exaggerated modernist myth is that when the audience gets to partake of the artist's vision, not only will they be able to share these insights but, eventually, the insights will radically transform them.

Jacques Rancière discusses this model in one of his books (Le spectateur emancipé, 2008), taking Martha Rosler's Bringing the War Back Home series of collages as one example. In Rosler's collages the Vietnam war is juxtaposed with interior scenes from comfortable American homes. The images expose a hidden reality, and Rancière argues that they evoke a sense of guilt in the viewer, as if they were saying: Look, here's a reality you don't want to see, because you know you are responsible for it.

As Rancière correctly notes, the scepticism about the efficacy of political art is quite reasonable; there is no straight line from perception, the viewing of an image, to the viewer being affected, and further on to understanding the political situation, finally resulting in action. This is overly optimistic. However, with Rancière's formulation, art creates "new configurations of the visible," of what can be expressed and what can be thought, which opens a new vista of the possible. It is a modest proposal, and I would argue that art is only one of the possible means to that end. Rancière is also rather critical of the kind of art projects that move out of art institutions, such as relational aesthetics and actionist art. As far as the goal is to have a lasting effect on the viewer, who becomes a participant in these art forms, I think relational strategies (if I may include Belmarsh Live and Anything to Say? in the category) have a much higher potential to deeply affect their audience than traditional art that works through symbolism and imagery.

PS

In my own artistic practice, I usually prefer to keep explicit topics of any kind at some distance. That's why I always struggle with those calls for work that insist on some theme to be addressed. For me, stating that my work is about this or that topic most often would feel dishonest, because only very rarely do I have some specific topic in mind when creating the work. That, of course, is hard to reconcile with overtly political art. There are exceptions, however, even one that I'm quite proud of. That is the installation Safe-space for Narcissists, which I had the opportunity to set up for one night in December 2019. Assange had been held in Belmarsh prison since April the same year, in solitary confinement most of the time, and I was following the case with keen interest.

The installation, of which unfortunately no photo documentation exists to my knowledge, featured a series of portrait drawings, prints, fictitious books, a mirror, a few other objects, and a soundtrack with various voices (Niels Melzer, Chelsea Manning, the late Andre Vltchek, and others), sometimes speaking about narcissism in general, or in various ways related to Julian Assange. Remember, one of the recurrent smears was that he was supposedly a narcissist. The same epithet has been used liberally in many other attempts of character assassination. Real narcissism, however, is bolstered by the attention economy which turns people away from engagement and activism. We still could use some more of the latter.